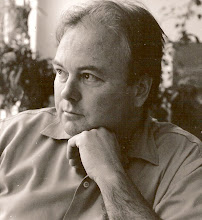

We mourn the passing of one of my dearest and oldest friends, Sombat (Paul)

Tasanaprasert, who died January 4, 2022, in Bangkok, Thailand. He had been in

and out of the hospital since June, 2021, after open heart surgery. Through

good times and some of my worst times, Sombat and his devoted wife Keila were

there by my side. During my 1980 murder trial, Sombat sat on the front row in

the courtroom, glowering at the parade of perjured witnesses. Throughout my

imprisonment, Sombat, Keila and their wonderful children have visited me in

prisons across the state as Father Time took his toll on us all.

I met Sombat in the Fall of 1968, my freshman year at the University of South

Florida, through my high school friend, Tony Puerta, from the Yucatan, Mexico.

He directed me to a large old wooden house north of USF's sprawling campus. I

could hear the din before we got out my car. It sounded like a crowd of people

were shouting at each other in half a dozen languages.

There were only about twelve of them, most of them beseeching Sombat to hang up

the phone so they could call their loved ones around the world, too. It seemed

a frequent occurrence, Sombat calling collect to his family in Bangkok and

talking for an hour or two every night.

Only about six international students actually stayed there, sharing the rent,

but at least a dozen would crash out on couches, sleeping bags and easy chairs

every night. It reminded me of what I'd heard about European hostels. Most of

those students were poor, and Sombat usually had people packed in his new

Oldsmobile, hitching rides here and there.

Sombat and I hit it off immediately, starting a friendship that would endure

for over fifty years.

We both loved playing golf, and USF had a beautiful golf course, a dollar each,

student rate, three dollars for golf cart rental. Monday mornings at 7:30 the

golf course was usually empty, after a busy weekend. We often had the place to

ourselves. We always wore shorts, to facilitate wading in the water hazards and

collecting the expensive golf balls lost over the weekend, then using them for

driving practice. One day Sombat wanted to see how long the electric golf cart

would last. We played forty-five holes before the golf cart gave out—

two-and-a-half eighteen hole rounds! We played fast with no one in front of us.

When we got back to the clubhouse, Sombat told the cashier the cart was no

good, it quit, and got the three dollar rental refunded.

Sombat was an excellent golfer, but an even better hustler. Neither of us had

much money, going to college and working part-time, me as a grocery store

bagboy and Sombat as the head bellman at the Hawaiian Village hotel resort.

When we got our golf clubs out of the car, two early bird professors asked if

we wanted to play a foursome.

Sure.

Sombat winked at me. Professors had money.

Sombat held up a five dollar bill. "You wanna put a five each on the front

nine?"

They did. We teed off.

Five dollars each wasn't much money, but Sombat had no intention of leaving it

at that. After a couple of holes he had the measure of our opponents.

He would tell me, "You want to get him to play against himself."

We were at a long par five that wrapped around a lake. You could play it safe

and hit two shorter drives along the fairway, or be bold and aim your shot

across the lake. If you hit the ball far enough, you could "drive the

lake," the ball crossing the water and landing much nearer the putting

green. It was easy to misjudge the shot, though, your ball splashing into the

lake.

If no one was coming up behind us, most Mondays we would stop at that hole and

practice driving the lake with a few dozen golf balls we'd collected at a

previous water hazard. Sombat was an excellent driver, and could hit the ball a

mile, it seemed. I was nowhere near his level, but I had my moments.

The better of the professors teed up his expensive golf ball, aiming to make

two safe shots around the lake, staying on the fairway.

"I'll bet you ten you can't drive the lake," Sombat said. Get him to

play against himself.

The professor stopped, looked at the lake, and turned back to Sombat.

"I'll take that."

He adjusted his stance, aimed more to the left, toward the lake, and swung. The

ball looked good, maybe two hundred yards, then plopped into the water five

yards from shore. The professor was so angry that he almost threw his expensive

golf club in the lake.

"Double or nothing?" the professor offered, after he'd cooled down.

He had come so close with his first shot. The second shot followed the first

into the lake. Sombat commiserated with the loser.

It went like that the rest of the round. The professors lost over a hundred

dollars, all their cash. Back in the locker room a chess set sat on a bench.

"You play chess?" Sombat asked. "Smart man like you probably a

grandmaster. You wanna win some of your money back?"

He did. He was a good chess player. But an hour later the chastened opponent

had to pull out his checkbook to cover his losses.

Sombat was an even better chess player than golfer.

My brother, Tom Norman, was a nationally-recognized taxidermist. People would

bring him deer heads and trophy bass to mount. One of his favorite subjects was

large eastern diamondback rattlesnakes, full body mounts of the menacing

reptiles coiled and poised to strike. One day Tom asked me if I wanted to go

snake hunting. Sure.

Rattlesnakes share habitat with Florida Gopher tortoises, dry sandy soil,

mostly covered with palmettos. Gopher tortoises dig tunnels at an angle,

sometimes twenty feet deep. If a Gopher tortoise abandons its tunnel, one or

more rattlesnakes will take it over. My brother would bring his tools: a

twenty-five foot water hose, a gasoline can, a snake hook — a cut-off broom

handle with a curved steel hook to pick up the snake or pin it down.

Tom would run the hose down the hole and jiggle it. He would hold his end of

the hose to his ear and listen. If there were any rattlesnakes down there, they

would rattle up a storm. Tom would pour an ounce or so of gasoline into the

hose, then blow the fumes down into the hole. Get out of the way! Any rattlesnake

in that hole would come pouring out. He would pin down the reptile with the

snake hook, then put it in the burlap bag that I held open.

What does that have to do with Sombat? I'm getting there. This is a classic

Sombat story that very few people know about.

A few days later I stopped by to see Sombat at the Hawaiian Village. All the

bellhops wore Hawaiian print shirts, and with his dark, exotic good looks many

people thought Sombat was Hawaiian. I told him about my snake-hunting

excursion. His face lit up. Sombat smelled money to be made.

"You have one of those snakes?" he asked.

"Not right now, but I can call my brother. He has them all the time."

And he did. That morning someone had brought him a rattlesnake over six feet

long. He agreed to let me borrow his snake that afternoon.

Sombat was keenly sensitive to the vibes others gave off, and he could easily

change the perceptions others had of him. He was a great actor. He was highly intelligent,

breezing through the most difficult math and engineering classes. He spoke

Thai, Lao, Greek, Arabic and English, that I knew of. He lived in Egypt before

coming to Tampa, and his sole brush with Hollywood was as Tyrone Power's movie

stunt double, pushing Gina Lollabrigida's rear end onto a camel about forty

times, until the director was satisfied and yelled, "Cut!"

I can't remember the name of the movie, but you can google it.

He could also appear stupid, disarming people who thought they were getting

over on him. They weren't.

Sombat could be the Charlie Chan-type stereotypical Asian with the broken

English who had difficulty understanding a condescending redneck, all the while

trying his best not to start laughing, or he could be the most sincere,

sensitive and generous person to a friend or family member who needed help. On

this afternoon of "Sombat and the Snake," he chose to be the

simpleminded bellhop toward the hotel manager, Sam Taub, a miserly man who

squeezed every nickel from a highly successful operation. The bellhops were

paid a mere pittance, relying on tips from the hotel guests.

I opened the trunk of my car and nudged the burlap bag with the snake hook,

setting off the rattlesnake within.

"Can you take it out?"

I grabbed the burlap bag and flung the rattlesnake onto the lawn, the reptile

coiling in its defensive mode, tail rattling, head erect, black tongue

flicking, ready to sink its sharp fangs into any life form stupid enough to

violate its space, like me. I didn't want to deal with a fatal dose of

neurotoxin. I was careful, following Tom's instructions. After assuring Sombat

the snake was alive and uninjured, and would perform its convincing act upon

command, I carefully put it back in the burlap bag, locked in my car trunk.

Sombat told me to say nothing, but to follow his lead. He strode confidently

into the manager's spacious office with thick red carpet and dark walnut

paneling. The manager was a small, middle-aged man with a comb over, sitting

behind a huge wooden desk, busily scribbling away at important papers when

Sombat burst in. This time he played the role of the dimwitted Thai bellhop to

perfection.

"Mr. Taub, Mr. Taub, we got real trouble," he said, breathless,

scared.

Mr. Taub was busy and cranky.

"What is it now, Paul?" he asked. Sombat was called Paul at work,

Sombat apparently being too hard for Americans to pronounce.

"Mr Taub, a guest saw a large rattlesnake by the pool."

"WHAT?" he yelled. “If that snake bites someone we can be sued. Are

you sure it was a rattlesnake?"

"Yes sir, it was a rattlesnake. It made those rattling sounds with its tail

and coiled up. Don't worry. I called my friend Charlie. He is a professional

snake hunter. He just charges one hundred dollars to catch a snake."

Mr Taub pulled out a hundred dollar bill from his wallet and tossed it on his

desk. I picked it up.

"Find that snake before it bites someone and puts me out of

business."

"Yes sir."

Sombat led me to the outdoor bar by the pool. We drank fruit juice coolers for

half an hour. I kept looking at the grouping of lush tropical flowers and

banana trees in a raised bed on the other side of the pool. Sombat had me half

convinced there was a real snake lurking near the swimming pool, waiting to

sink its fangs into the ankle of an unsuspecting tourist. He grinned at me.

"It's showtime," he said. I got the burlap bag with the angry

rattlesnake inside out of the trunk, grabbed the snake stick, and hurried after

Sombat, headed for the office.

"Mr. Taub, Mr. Taub, good news. My friend caught the rattlesnake. Show

him, Charlie."

I don't know what the hotel manager expected to see when I flung open the

burlap bag, perhaps a dead snake, but the last thing he expected was a six foot

long furious rattlesnake coiling up on his plush red carpet, itching to strike.

Mr. Taub was afraid of snakes, especially venomous ones. Screaming, he climbed

onto his office chair, yelling, arms waving.

"Get that thing out of my office," he continued to yell.

I pinned down the serpent's head with the hook, carefully grasped it’s head,

and dropped it into the bag, pulling the drawstring tight. Mr. Taub poured

himself a strong drink from a bottle he took out of his desk.

"Bad news, Mr. Taub," Sombat said.

"What now?"

"Rattlesnakes mate for life," Sombat said with a straight face.

"My friend caught the male, but the female is still out there."

The manager pulled out another hundred dollar bill. "Find that thing. Kill

it."

"Yes sir."

Before I tell you about Sombat's first meeting with Chuck Norris, I must tell

you about Ron Slinker and Martial Arts Institute, Inc.

Bruce Lee's movie, "Enter The Dragon," ignited a boom in karate

students nationwide. At the University of South Florida they had classes in

Shotokan karate, a Japanese style, but I didn't like it. The Joon Rhee

Institute taught Taekwondo, a Korean karate, which I much preferred. The head

instructor was an excellent teacher, but a poor businessman. The school was on

the verge of closing. Several fellow students, affluent businessmen, offered me

the chance to invest in a new company, Martial Arts Institute, Inc., that would

be the first in a chain of karate schools based in Tampa.

I invested my savings in the company and joined the board of directors as

treasurer. The plan was to take over existing karate schools run by good

instructors but bad businessmen. Later we would open new schools. Ron Slinker's

Yoshukai karate school was our first acquisition.

Ron Slinker was a 6-foot 3-inch, 240-pound Fourth-degree karate black belt,

Florida heavyweight black belt karate champion, black belts in judo and aikido,

and former U.S. Marine Corps Pacific boxing champion. In his first book, Dwayne

"The Rock" Johnson, mega movie star, said that Vince McMahon,

president of the World Wrestling Federation, sent him to Tampa to train with

Ron Slinker, learning to be a professional wrestler. "The Rock" said

that Slinker was the baddest genuine bad-ass he'd ever met.

"The Rock" never met Sombat.

In early 1974 I went to Joe Corley's "Battle of Atlanta," the South's

largest full-contact open karate tournament, seeking qualified Taekwondo

instructors for schools we wanted to open in Florida. This was during the

beginnings of American professional kick boxing, and I was invited to represent

Florida in the formation of the Southeast Karate Association.

Joe Corley introduced me to Chuck Norris. We had breakfast together at The Omni

Hotel. This was after Bruce Lee got Chuck into the movies, although he was not

yet known as a movie star, but five-time undefeated world karate champion.

Chuck and I hit it off, and we had a good time with other karate champions

checking out the buzzing Atlanta nightlife.

I invited Chuck to come to Tampa in November as a guest celebrity at a martial

arts exhibition we were planning.

"I've never been to Tampa," he said, agreeing to come to Tampa for a

few days to help promote our businesses. As easy as that.

Meanwhile, Slinker was in training to fight Harvey Hastings, the winner to

fight the reigning American kick boxing champion, Joe Lewis. I was talking to

Sombat one day about Slinker's problem finding sparring partners to practice

against. He would beat up his hired sparring partners so badly in the first

round that they couldn't make it to round two. He was paying $100 a round to

spar, three-round minimum.

"Kick boxing?" Sombat said. "$300? I'll do it."

"You will?"

"In Thailand, I went into 'Muay Thai' training camp at twelve. I kickboxed

professionally three years. Heavyweight champion. Not many heavyweights in

Thailand. I lost one fight, decision, in the north. Referees cheated."

"Are you kidding me?" I'd never heard Sombat say a word about kick

boxing. He'd played on the USF soccer team and had an incredible kick, but it

never occurred to me that my mild-mannered friend who never raised his voice

could be a ''Muay Thai" kickboxer.

It turned out that Sombat wasn't mild-mannered in the boxing ring.

I told Slinker that I'd found him a real kick boxer for a sparring partner.

"Thai kick boxer? Those boys are bad. How much he weigh?"

"Six-one, one ninety-five."

"When can he start?"

"Tomorrow okay?" I said. "Our school, ten a.m."

I was really worried that Sombat would get hurt, and it would be my fault. What

could I possibly say to Keila?

I need not have worried. Slinker was the only one that went to the hospital.

I'm not going to describe 'Muay Thai' kick boxing. I'm sure Sombat's family in

Thailand have seen many matches, and YouTube videos are easily accessible. It

was my first experience, though, and I was gobsmacked. Thai kick boxing is like

fighting a man — a very strong man — wielding a baseball bat. Every time you

get in reach of the baseball bat the man hits you — hard — on whatever body

part intrudes in his space. The baseball bat was Sombat's right leg.

Sombat hadn't fought in ten years, but none of the dozens of students or

several black belt instructors would believe it. He'd never fought a

"karate expert," either, but as Slinker absorbed kick after powerful

kick from Sombat's shin bone, he didn't look much like an expert in anything

besides getting knocked down.

After Slinker gave up and was taken to the hospital, our head instructor, Doug,

asked Sombat if he would show him some of his moves. Sure.

After Doug took his beating, four of the top black belts in Florida gamely

asked for chances against Sombat, and Sombat put each one away without breaking

much of a sweat.

I couldn't let those other guys go down without me, so I took my turn. Stupid

me.

"Sombat, we're friends, right?"

"Of course. Best friends."

"You have to show me this ''Muay Thai" stuff, but take it easy on

me."

You wouldn't believe the purple bruises that took a couple weeks to fade away.

After Slinker healed up, he sparred with Sombat twice more, with the same

results, even wearing so much protective padding that he looked like the

Michelin Man.

Slinker was so demoralized by the beatings he'd

taken in their sparring sessions that he dropped out of the match with Harvey

Hastings, returning to teaching his classes.

I reserved the Fort Hesterly Armory in Tampa for a November, 1974, Saturday

night date. The Armory hosted the weekly Tuesday night professional wrestling

matches and the occasional boxing match, with around 6,000 seats. It had never

hosted matches like ours. The words, "mixed martial arts," had not

been coined yet, but that's what our exhibition was, the first mixed martial

arts matches in the South: judo versus aikido, wrestling against boxing,

Japanese karate versus Taekwondo, karate versus kick boxing, along with

demonstrations of weaponry.

Chuck Norris said that Glen Premru , the highest-ranking non-Oriental karate

weapons expert in the world, was the best karate demonstrator he'd known.

Premru was under contract with Martial Arts Institute for promotions, using

nunchakus, and cutting watermelons in half with a samurai sword — the

watermelon balanced on the chest of a volunteer, horizontal between two chairs.

He was there the day Sombat gave Slinker a lesson in kick boxing, and said

Sombat was the toughest kick boxer he'd ever seen.

We had a group of students holding welcome signs when Chuck Norris got off the

airplane at Tampa International Airport that Friday afternoon. Before we took

Chuck to his suite at the Hawaiian Village, he was interviewed by the sports

directors of three TV stations, then we went to our main school on Busch Blvd.

for more promotions.

We had a great crowd of students waiting to meet Chuck Norris. He signed

autographs and posed for photos. Sombat gave a brief demonstration of kick

boxing, two adult men held the eighty-pound punching bag steady as Sombat

kicked the bag almost in half. When the stuffing began coming out, Sombat

stopped.

Grinning widely, Chuck Norris introduced himself and shook Sombat's hand.

"I'm glad I never faced you in a match," Chuck Norris said, dead

serious.

The feature match was karate versus "'Muay Thai" kick boxing, Herbie

Thompson, from Miami, against Sombat. Sombat's preparation before the match was

a fascinating ceremony, almost religious in nature. Unfortunately, Sombat lost

the match to an excellent black belt fighter that he should have beaten.

Sombat was a devout Muslim. He went on the "Haj," the pilgrimage to

Mecca, many times. I never learned that until years later. I knew he had lived

in Egypt for a time, and been in the movie, but didn't realize he spoke fluent

Arabic until one weekend he visited me, and asked me to introduce him to a

Syrian prisoner visiting with his family. I did, then I was surprised when the

family began excitedly talking in Arabic for several minutes. Later on, my

Syrian friend told me, "You have a very impressive, important friend."

I didn't understand completely what he meant until many years later, in prison,

when Sombat's wife, Keila, told me about when she went to Thailand for the

first time, the reception.

Buddhists make up around ninety percent of Thailand's population. They dominate

the civilian government. But Buddhists are pacifists, which means the ten

percent Muslim minority dominates the Thai military.

When we were college students, it often amused me at how other Thais behaved

around Sombat. Tampa had a surprisingly large population of Thais, and Sombat

patronized a gas station on Busch Blvd. run by a family from Bangkok. When

Sombat pulled up to the gas pumps, his car would be suddenly surrounded by

several enthusiastic, deferential young men who filled his tank, polished the

windshield, checked the tires and oil, providing great service. The other

customers didn't receive such attention. We went into the store to buy some

snacks, and the female clerk beamed at Sombat, chattering in their native

tongue. I told him once, "You're a rock star." I didn't realize then

how close I'd come to the truth.

Keila told me that when Sombat brought his family to Thailand for the first

time, he had been away from home for many years. When the passenger jet landed,

Keila noticed a crowd of people waiting and watching. A man in a military

uniform boarded the plane--a general in the Thai army --ecstatic about Sombat's

return and delighted to meet Sombat's family. He was obviously a longtime

friend.

Keila asked the general why all those people were gathered outside.

"They've come to welcome Sombat home."

Keila said that whenever they went some place in Thailand it was the same way,

crowds of people greeting Sombat. Some of that was because of his kickboxing

fame from many years before, but it was also that Sombat was a religious leader

to his fellow Muslims.

Sombat was also a great cook of Thai dishes. One day Sombat and Keila invited

me over for a traditional Thai meal featuring curry chicken. When I walked into

the kitchen my eyes began burning. I thought Mexican food was hot. Thai cooking

made Mexican food taste bland!

We sat down at the table as Sombat served the food. A very large glass of iced

tea was next to my plate. A large pitcher of more ice tea was placed in the

center of the table. I made some crack to Sombat about how he must really love

tea.

As he dished out the steaming curry chicken he smiled, saying, "You'll

drink that glass, and more."

He was right.

The last time we were on a golf course together, Sombat and Keila invited me to

join them and several Thai friends to the Bardmoor Country Club in Pinellas

County for a professional men's and women's golf tournament before my arrest in

1978. All the famous golfers of the past twenty years were there: Arnold

Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Lee Trevino, Sam Snead, Nancy Lopez, and many others I

can't recall. I was surprised how accessible and open the famous golfers were

to their fans, talking, signing autographs, and posing for photos. Sombat had a

good time--we all did, but looking at Sombat I knew he would nave been much

happier if he'd been on the golf course with a club in his hand, convincing

some millionaire pro to bet against himself.

There is much I don't know about Sombat. Over four decades incarcerated in

harsh prisons separates one from the everyday lives of family and friends.

Years ago, at one of our infrequent visits, when Andie and Adrie were little

children climbing on Sombat's lap, he said to me, "If something happens to

me I want you to look after my family."

"Of course," I said.

"You are godfather to my children."

Although there is little I can do to help my friend and his family from inside

these prison fences, I take my vow seriously. Perhaps one day I will be free,

and my wife Libby and I can sit down with Keila and the children, and they can

tell us stories I had missed.

Sombat was a great man, devoted husband, father and friend. He affected all our

lives, and we will never forget him.

Rest in peace, dear friend.

Charles Patrick Norman -- January 24, 2022

No comments:

Post a Comment